|

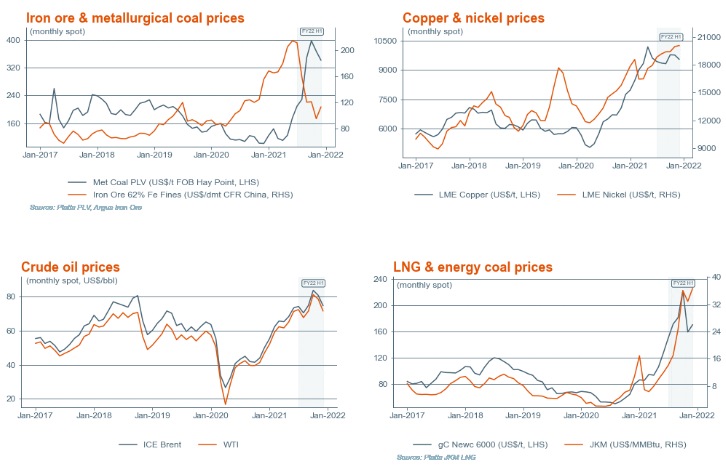

FY22 half year 15 February 2022 Six months ago, at the time of our full year results for the 2021 financial year, we reported markedly improved operating conditions for the majority of the portfolio. Those commodities that had performed strongly in calendar 2020 had built on that momentum. Those that had lagged somewhat in calendar 2020 were showing clear signs of entering a recovery phase. As a result, most of our major commodities were trading at prices that were close to, or above, our estimates of long term equilibrium. As we release half year results for the 2022 financial year today, developments over the last six months make it more difficult to generalise about the portfolio in a narrative sense. The half year was characterised by (yet more) extraordinary volatility, but instead of a shared, albeit staggered recovery pattern, highly idiosyncratic trends have emerged within the energy and non–ferrous commodity clusters, as well as within the steel making raw materials complex. Nevertheless, and the aforementioned volatility notwithstanding, the statement that “most of our major commodities are trading at prices that are close to, or above, our estimates of long term equilibrium”, is still – remarkably – absolutely valid.

We expect the demand–supply balance to remain relatively tight in both copper and nickel. Iron ore moved into surplus in the second half of calendar 2021, and, on balance, is likely to remain in that state across calendar 2022. We see no clear directional bias for oil prices from current elevated levels, while LNG prices are more likely to move lower than to sustain (or set new) all–time highs. Metallurgical coal prices have also achieved all–time records on multi–regional, multi–causal supply disruptions. The degree to which these ease, and by when, is the key swing factor for the coming year. Potash seems poised at the crest of its stunning bull wave, driven by strikingly positive downstream fundamentals at a time of both constrained and uncertain supply. There is obviously still some residual uncertainty as to how vaccine deployment and the policy and behavioural response to the newer, highly transmissible strain of COVID–19 will interact over the coming quarters. There is also a higher level of macro complexity to deal with than in the recent past, as the world’s two major systemic growth engines – the US and China – adopt diametrically opposite counter–cyclical policy stances. So while the “uncertainty discount” in the risk appetite of households and businesses we have noted in previous communications is definitely fading, it is doing so in uneven fashion across the world, and new vectors of uncertainty have arisen, such as the situation in Ukraine. Looking beyond the immediate picture to the medium–term, we continue to see the need for additional supply, both new and replacement, to be induced across many of the sectors in which we operate. After a multi–year period of adjustment in which demand rebalances and supply recalibrates to the unique circumstances created by the COVID–19 shock, we anticipate that higher–cost production will be required to enter the supply stack in our preferred growth commodities as the decade proceeds.

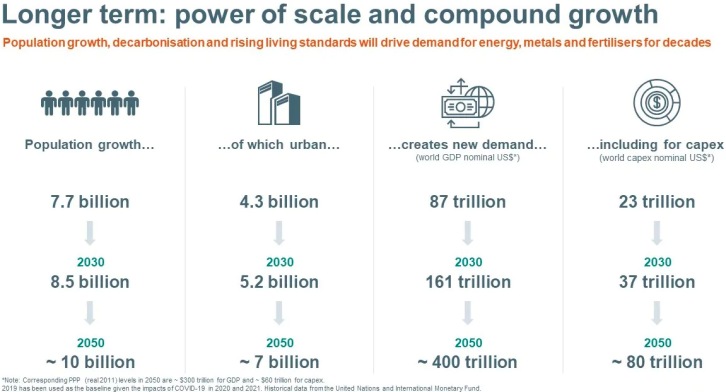

Image by BHP The projected medium–to–longer term steepening of some industry cost curves that we monitor, which may be amplified if carbon pricing becomes more influential in both demand and supply centres, can reasonably be expected to reward disciplined and sustainable owner–operators with higher quality assets featuring embedded optionality. We confidently state that the basic elements of our positive long–term view remain in place. Population growth, urbanisation, the infrastructure of decarbonisation and rising living standards are all expected to drive demand for energy, metals and fertilisers for decades to come. We continue to see emerging Asia as an opportunity rich region within a constructive global outlook. From a pre-pandemic baseline, by 2030 we expect: global population to expand by 0.8 billion to 8.5 billion, urban population to also expand by 0.8 billion to 5.2 billion, nominal GDP to expand by $74 trillion to $161 trillion and capital spending to expand by $14 trillion to $37 trillion. Each of these basic fundamental indicators of resource demand are expected to increase by more in absolute terms than they did across the 2010s. By 2050, we project that: population will be approaching 10 billion; urban population will be approaching 7 billion; the nominal world economy will have expanded to around $400 trillion, with one–fifth of that – i.e. around $80 trillion – being capex.

Furthermore, with fiscal and monetary policy makers in key economies having shown their commitment to a reflationary agenda, the secular fundamentals that make our industry attractive may well be amplified this decade. In line with our purpose, we firmly believe that our industry needs to grow in order to build a better, Paris–aligned world. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) stated on August 9, 2021 that “Unless there are immediate and large–scale greenhouse gas emissions reductions, limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius will be beyond reach”. As illustrated by the scenario analysis in our Climate Change Report 2020 (available at bhp.com/climate), if the world takes the actions required to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees, we expect it to be advantageous for our portfolio as a whole. And it is not just us. What is common across the 100 or so Paris–aligned pathways we have studied is that they simply cannot occur without an enormous uplift in the supply of critical minerals such as nickel and copper. Our research also indicates that crude steel demand would be a net beneficiary of deep decarbonisation, albeit not to the same degree as nickel and copper. And some of the scenarios we have studied, such as the International Energy Agency’s high profile Net Zero Emissions scenario, would be even more favourable for our future–facing non–ferrous metals than what is implied by our own work to date: albeit with different assumptions and potential impacts elsewhere in our portfolio. In this regard, we welcome the fact that the share of global emissions now covered by national level net zero or carbon neutral national ambitions has reached 85%, although we continue to monitor whether these ambitions will crystallise as tangible action. This includes our key Asian customer centres of Japan and South Korea (2050), China (2060) and India (2070). Less positively, the share of global emissions that are “priced” is much lower, at 25%, and the average price itself, at $26/t, is still too low to sponsor the radical change in the energy and land use system that is required if ambitions are to be met. Against this backdrop, energy transition investment, as defined and estimated by Bloomberg NEF, totalled $755 billion in 2021, up from $595 billion in 2020. Easier-to-abate sectors – renewable energy and electrified transport – attracted 85% of those funds. Technology with the potential to unlock gains in harder-to-abate corners of the energy system, such as Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS) and hydrogen, attracted just over $4 billion collectively. The aggregate and sectoral figures are both promising (in terms of growth) and underwhelming (in terms of level) at the same time. As the true costs of a lack of climate action are progressively recognised, and demographic change proceeds, we anticipate that a popular mandate for closing the gap between ambition and policy action will progressively emerge. Here we note that the younger generations that will define our future – both Millennials and Generation Z – are more concerned about climate change than their elders in both East and West. They are also more favourably disposed towards globalisation. That is good news for the international cooperation that will be required to limit global warming in the most efficient manner. And it also offers hope that the current wave of populist economic nationalism that we observe, which represents a headwind for long term global prosperity, may also retreat in time. Now: add each of the generally constructive foregoing themes to the fact that the resources industry as a whole has been disciplined in its allocation of capital over the last half decade or so. With this disciplined historical supply backdrop as a starting point, any sustained demand surprise seems likely to flow almost directly to tighter market balances. Investment that seeks to abate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and/or adapt to, insure against and mitigate the impacts of climate change is expected to rise to become a material element of end–use demand for parts of our portfolio. The electrification of transport and the decarbonisation of stationary power are expected to progress rapidly, and the desire to tackle harder–to–abate emissions elsewhere in the energy, industrial and land–use systems is building. Comprehensive stewardship of the biosphere and ethical end–to–end supply chains will become even more important for earning and retaining community and investor trust. The ability to provide and demonstrate social value to our operational and customer communities is both a core enabler of our strategy and a source of competitive advantage. Against that backdrop, we are confident we have the right assets in the right commodities in the right jurisdictions, with attractive optionality, with demand diversified by end–use sector and geography, allied to the right social value proposition. Even so, we remain alert to opportunities to expand our suite of options in attractive commodities that will perform well in the world we face today, and will remain resilient to, or prosper in, the world we expect to face tomorrow. Global economic growth The world economy contracted around –3% in calendar year 2020 and we estimate that it bounced back by a little less than +6% in calendar 2021. Our starting point for world growth in calendar 2022 is +5%. The IMF’s latest projections for 2022 are roughly –½% below this. The worldwide impact of the Delta outbreak, China’s weak second half and a range of supply bottlenecks all restrained activity relative to our expectations at the outset of calendar 2021, when our base case was that growth could comfortably exceed 6%. Within the year, we were tracking well above our year–opening base case in the first half, but we fell below it in the second. Against this backdrop exchange rate volatility has been relatively modest. Compared to the levels prevailing at the time of our full–year results, the US dollar index (DXY) was roughly 6% stronger as the first half of financial year 2022 closed. In real trade weighted terms, as of December–2021 the US dollar has increased in value by roughly 5% from June–2021, and was almost on par with the recent peak achieved during the COVID–19 panic of April–2020. US dollar strength was most clearly expressed against non–China emerging markets. The Chinese yuan appreciated by around 6½% against the US dollar in calendar 2021. International trade collapsed by around –5 % in calendar 2020. The strong recovery from the nadir, which began in the second half of calendar 2020, has continued essentially unabated since, with Jan–Nov 2021 data showing growth of around 11% year–to–date YoY. As of November 2021, the volume of world trade was 4% above calendar 2019 levels. Exports from developing economies are 8% above 2019 (China 21%) and exports of developed countries are up 1% on the same basis. Unit prices of world exports are up 13% on the calendar 2019 level. As global policymakers increasingly shift their attention to calibrating a delicate exit from the extraordinary policy settings they delivered in extremis, while keeping a weather eye on inflationary momentum, it is worth recalling that the underwhelming performance of the global economy in calendar year 2019 was in large part due to weak international trade and the associated negative impacts on business confidence. Trade is the essential lubricant of global economic growth, and a reflationary agenda ought to embrace that fact. In addition, we strongly encourage policymakers to prioritise structural reforms at home as the surest route to sustainable productivity growth, and ultimately, prosperity, coming out of COVID–19. Remaining open to the cross–border flow of people, goods, capital and ideas is vital to this end: free trade based on comparative advantage, competition, productivity and innovation are close companions. Some of the “bad” inflation we will refer to throughout this article is the direct or indirect result of natural flows of physical production inputs being impaired. The sooner the logic of comparative advantage in international trade and entrepreneurial “pull” migration can again be granted full play, with due consideration for public health concerns of course, the better. These arguments highlight the importance of continued and vocal advocacy for free trade, open markets and high quality national and multilateral institutional design by corporations, governments and civil society. A key feature of the global economic recovery in calendar 2021 was a series of upside surprises in measures of economy–wide inflation, with both headline CPI and upstream (PPI) readings elevated. Supply elasticity in a range of goods–producing and distributing sectors has fallen well behind the speed of the turnaround in demand. Normal movements of labour within and across countries to match with job opportunities has also been impaired. As a result, productivity has suffered, market balances have tightened and in some instances, scarcity pricing has emerged. These factors have driven the underlying cost base of some of the world’s most essential end–to–end value chains higher – for example petroleum products, construction materials, semiconductors, automobiles and food – and the associated distribution industries (principally land, sea and air logistics). And the curve has been steep. As of December 2021, consumer and producer prices in the US were tracking around 7% and 10% YoY respectively. The most recent updates on producer price inflation in the EU, Japan, China and India are distinctly elevated at 26%, 8%, 10% and 14% YoY respectively (rounded). Major commodity producing countries such as Chile, Canada, Brazil and Russia are seeing equivalent or even higher outcomes. Australia is presently an outlier with PPI at “just” 3.7% YoY and CPI at 3.5% YoY in the December quarter. Both of these readings are obviously subdued by current international standards, but the Q4 CPI was still running well in advance of official forecasts made just a short time ago, in November–2021. That drove a +1 percentage point upgrade to the RBA’s June–2022 YoY CPI projection released in early February–2022. We anticipate that “bad” inflation due to supply bottlenecks in key value chains will remain challenging in calendar 2022, with only tentative signs of easing expected by the end of the period, with clear potential for some spillover to calendar 2023 in certain sectors. Additionally, we anticipate that “good” demand–led inflation will endure for some time, leading to higher average inflation outcomes across the 2020s than what we experienced across the 2010s. That view is partly due to both our constructive underlying view of world growth and the likely performance of the resources industry – the underlying source of upstream pressure in physical value chains – following a half decade (and counting) of disciplined capital allocation. This thesis also relies on the fact that policy makers have altered their medium–term strategies with respect to both monetary and fiscal policy in a way that is more accommodative of a moderate lift in core inflation than the frameworks they are replacing. The impact on private sector confidence of this pro–growth policy stance will be positive and durable, in our view. Moderately higher inflation on average across the decade will also assist with the passive repair of strained public sector balance sheets. The extra half a percent or so on the global inflation rate that we envisage for the 2020s will increase the size of the nominal global economy by around $8 trillion by 2030, or 9% of 2019 GDP. The phenomenon of structural “greenflation” is also real and will, we believe, impact upon price dynamics and the wider economy in the medium and long run. There is more than one definition of this concept in circulation, so let us be clear what we mean by this. “Greenflation” is the process whereby the global price level progressively internalises the costs and benefits of both action and inaction pertaining to the impact of climate change and stewardship of the biosphere. It is a fact that the global price level does not yet fully internalise the social cost of carbon, the emissions of other greenhouse gases (GHGs), other activity that negatively impacts upon natural wealth, such as deforestation and biodiversity loss, or degrades other eco-system services, or the future capex bill for governments and business to deliver on all aspects of the energy transition, from the provision of critical minerals to building the green infrastructure of the future. To date, regions or individual actors with positive footprints also find it difficult to quantify, let alone monetise their virtue. The process of internalising these costs, and remunerating positive actions, whether the process be swift or gradual, will inevitably alter the dynamics of price formation in all corners of the economy. Full report BHP press release

|